I usually talk about video games on this blog, but today I want to talk about a board game that’s very special to me.

Go is the oldest known board game in human history that’s still played today, dating back to around 2500 years ago. It was invented in China, and they call it wéiqí (围棋), meaning “encirclement board game”. Not super catchy, but it gets the point across. The game is massively popular in Japan (where they call it igo / 囲碁 / いご) and Korea as well (where they call it paduk / 바둑); those three Asian countries each have gigantic professional leagues, formal schools of the game, and even cafes and other spaces dedicated to it where you can always find players. It’s only popular in America among math nerds and people in their 60s and 70s. Chalk up yet another way in which we’re the most ignorant, backwoods country on the planet.

There’s not a lot of rules, and those rules are pretty simple to learn and understand. By combining these simple rules, however, Go becomes a beautiful and compelling game of staggering complexity and strategic depth. The game was historically said to be a kind of canvas on which everything in the universe could be represented, and I think it’s neat that it turns out there are more possible board positions than there are visible protons in the known universe.

Rather than simply regurgitating the contents of the Wikipedia article I linked above, or talking at length about the rules and particulars, I want to instead talk about what Go is to me. This isn’t so much a review or explanation as it is a memoir. And I’m gonna ramble a bit about martial arts and competition, too. If you’re interested in learning Go, you can find many better teachers than ol’ grandma Applebaps. I’m like 20kyu on my best day (that’s not very good). I recommend starting over at Sensei’s Library. It will be well worth your time.

I’d dabbled here and there with Go in brief flirtations when I was much younger, but never really understood it or had it grab me. I first became seriously interested in Go in college. I was working on a bachelor’s degree in mathematics, and I joined up with the math club. We’d meet after classes every month, talk about interesting problems and theory, math news, that sort of thing. And there was one guy in that group who was super passionate about this board game and trying to get everyone into it. I recognized the board and the pieces, and I realized I’d played it before. With fresh (and more educated) eyes, the game did have a certain mathematical appeal in its patterns, its life or death “cases”, its joseki (ideal set exchanges of play). It had an air of being potentially solvable but always elusive, relying on a blend of logic and intuition to play it well. I was immediately captivated, and started devouring anything and everything I could get my hands on related to the game while playing it a lot. I’ve been hooked ever since.

Here’s the thing about my personality, though: I’m a sore loser. I know this about myself, and I’ve tried very hard to reign it in over the years, because nobody likes That Person. But losing in any competitive game burns me, a lot. Go, for all its philosophical complexity, is still an adversarial game with one winner and one loser. And more often than not, I’m the one losing. There’s a saying (Go has lots of these) that you have to lose 100 times before you can start to learn the game. I’m not sure exactly how many times I’ve lost, but it feels like a thousand times. With Go, losses are harder for me to take than they are in almost any other game.

The reason for this is that Go’s simplicity gives rise to one of the most direct mind-to-mind conversations possible in competitive gaming. When you see the way someone plays Go, and you understand the game, you feel as though you’re really getting a sense of who they are. The flipside of this is that when you play poorly or clumsily, you feel as though you’re stammering uncontrollably, failing to express yourself properly. And when you lose, it feels as though YOU yourself have somehow lost. Not just at Go, but somehow you’ve lost at life, your core philosophy of play has been found wanting. It can be very frustrating and demoralizing.

I’ve seen a lot of talk over the years in America surrounding the “play to win” philosophy first seriously espoused by David “Sir lin” Sirlin Dot Net “Dot” Com “Lin” David Sir to Win. Dot Win. Help

Okay.

This idea, of being a “true warrior” who does whatever it takes to win and discards ideas like “honor” and “fun” has a long history. The oldest particular example that springs to mind is Miyamoto Musashi’s “Book of Five Rings”, in which he justifies his idea of using a sword in each hand, rather than focusing on holding one sword with both hands, because it’s more effective on the actual battlefield to have that extra weapon. At the time, Musashi’s ideas were revolutionary, absurd even, among a Japan stuffed to bursting with schools of swordplay all focusing on (and profiting from) teaching people to use a single blade.

Musashi was a soldier first and foremost, and he was primarily concerned with staying alive to cash his pay cheques (in a manner of speaking). When you’re talking about coming out on top of a life-or-death situation, it’s obvious that you’d want to do whatever it takes, right? Surely, the same principle applies to any competitive endeavor. You wouldn’t want to go into a competition intending to lose. So, you want to use any exploit, focus on only the best tactics, use the best tools at your disposal, practice constantly, and use everything you’ve got ruthlessly and completely at all times, against all comers. Anything less tarnishes your skills, dulls your reactions, keeps you at a lower level of development, and does a disservice to your competitive community, right? That’s the way of the true warrior, the one who wins. Those who doubt you are “scrubs”, unskilled and undeserving of your attention unless they also rise to the challenge.

Here’s the difference between Musashi and Sirlin, though: Sirlin is not fighting in wars as an infantryman on the ground. He’s not trying to avoid being painfully disemboweled, maimed irreparably, or killed by the swing of a sword. He’s playing goddamn video games. If you’re a swordswoman and somebody tells you you should hold your sword a certain way because it’s “honorable”, and you know that doing it that way will get you killed, you absolutely should reject that person’s teaching. One hundred percent. The same idea just does not apply, however, to playing games with your friends. If you start going full Sith Lord on your buddies on Smash Night, very soon you won’t have anyone who wants to play games with you that isn’t also a Sith Lord about it.

I’m kinda going off on a tangent here, but when I think about something like a fighting game tournament (something I really enjoy watching), the closest comparison to that sort of event in my mind is a martial arts tournament (something I’ve participated in when I was younger). Martial arts tournaments generally have safety measures and rules in place to prevent people from being seriously injured, because at the end of the day, martial arts are no longer warfare-related. Nobody is living or dying because of them. Martial arts styles aren’t closely-guarded government secrets anymore. We have guns and bombs, planes and submarines, all kinds of stuff. And you can look up the deep secrets of any martial art you could ever want to know, on Youtube. The point of martial arts competition is now a kind of historical re-enactment, it’s a way of showing reverence for a part of our past as humans, celebrating and preserving it together in a way that’s no longer a matter of life and death.

So, we wear pads and mouth guards, we don’t strike to kill, we don’t hit people in the throat or genitals, or bend their joints backwards, like you would have back in the day. Because that’s awful, it’s no fun for anyone involved, and it’s not the point. But on the other hand, Americans love MMA (which pretends to be “super real”) and reject pugilistic boxing more and more these days. They fundamentally either don’t understand the point of martial arts in a modern context, or they have an insatiable thirst for blood that isn’t slaked by the relatively-“tame” sweet science anymore. What would they think of a karate tournament for children, then, where nobody is trash talking or crying or even bleeds at all? Look at these weak little sausages, unfit to be true American warriors. They’ve banned kicks to the groin! This is no true competition. Et cetera.

There’s also a division in the martial arts between “hard” and “soft” styles, and maybe my attitude is a result of having switched over to a soft style as I got a bit older. When I was younger, I went from Karate and Tae Kwon Do to Muay Thai, in an escalating progression of violence and self-destructive training. I tried to make myself into a weapon. I was playing to win, looking for the most effective techniques. But, why though? Looking back, I can see that my drive to inflict pain, to reject humanity and become a weapon, were the result of deep-seated problems in my self-image. It was the way I dealt with my traumas and emotional pain. I had something to prove, and a burning hatred of other human beings that I could only express through violence. That doesn’t mean that everyone who practices a “hard” style is the way I was. Or even that everyone who “plays to win” is that way, either. But I think it bears consideration and reflection, if you are someone who embraces those styles or that way of playing games. Take a look at what kind of human being those ideas make you into.

These days, I’m still a dedicated martial artist, but my days of violence are behind me. I practice Xingyiquan (形意拳) instead of Thai boxing, working on deep internal muscles and the cultivation of qi, something I go back and forth on whether or not I believe in. My hips, shins, ankles, knees, and hands didn’t escape all damage. As I get older, I’ll have to pay the price more and more for the first quarter of my life spent smashing my extremities into things. And I lose a lot at fighting games and at Go. That’s because I realized that there’s more to life than competition, that I’m a human being first and foremost. But the mind poison that is “playing to win” does not let go easily, it forms a web and anchors itself into your brain with circular justifications that sound compelling even though they are completely irrelevant to modern life as a complete person. As such, I still find myself getting salty as hell when I lose in competitions, in part because I blame myself for not going all out or not putting in the time to truly become the best. I’m a scrub, my brain tells me, why am I even bothering. I’m continually working on being nicer to myself, and turning away from the “dark side”.

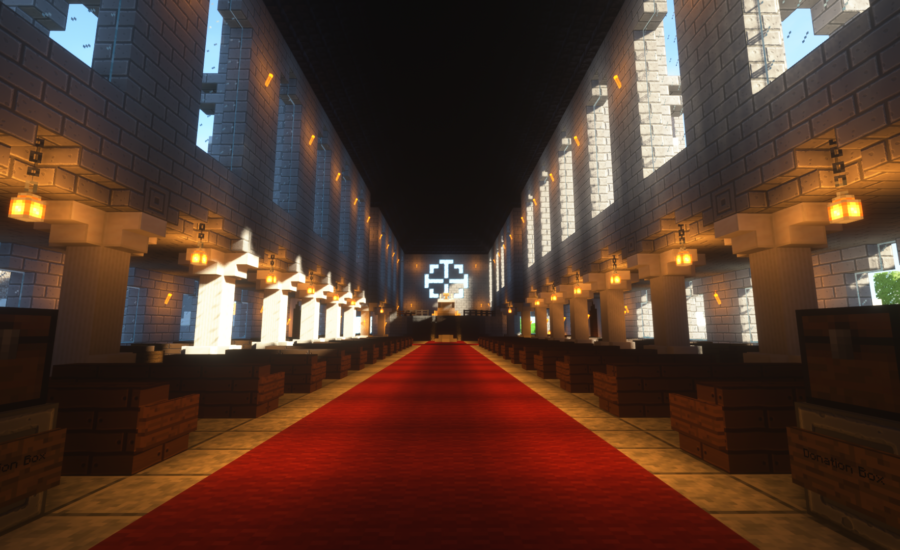

So, what is Go to me? Go is a really fun game. It’s frustrating, and it’s difficult. It generates beautiful patterns to look at on the board, and stimulates your mind with tricky situations and puzzles to solve that are always changing. It’s easy to teach someone how to play it, but I have a hard time unlearning my old habits and not crushing new players immediately. At the same time, I’m not good enough to truly stand against anyone who’s actually good at the game. And I never really get to practice it, so I’m always rusty. It’s a game that can be played online in numerous places, with people all over the world, but which for me only has real meaning when played on nice-smelling wood, with stones of particular materials that sound a certain way when placed, whose weight I can feel in my hands. And it’s a game that I’m constantly having to explain to my fellow Americans, who don’t care about it and have no lasting interest beyond its “exotic” quality.

It’s also a game at which computers have finally surpassed human beings in skill. It was the last such holdout, actually, which previously was the source of great pride to many Go players, myself included. Every other board game was solved long ago, but Go, the oldest and most complex game, was the one thing we had left. Inevitably, though, people have finally started losing at Go to AI a few years ago. Many players had to ask themselves, what’s the point? If we can’t be the best, why should we play? What is it that distinguishes us now, as a species?

Here is my answer.

You know you can just play games for fun, right?